St Hugh’s Library is home to unique treasures dating from the 15th century. Formed by chance rather than by design, St Hugh’s rare book collection has become a cabinet of curiosities, housing books of unique themes including that of exploration, magic, literature, natural history, and ghostly apparitions. Each book represents more than just what is relayed on the page but an entire history of those who read and cherished the item in their day.

This exhibition will highlight a few of the fascinating histories contained within each book such as the evolution of natural history from bestiaries to bird books, the obsession with death during the Early Modern period, how alchemy transformed the process of scientific methodology, and power and language through the Norman Conquest.

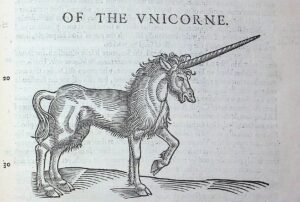

The incredible text pictured below is what is known as a bestiary, or a compendium of “animals.” Originating in the ancient world, this type of work grew in popularity in the Middle Ages. A bestiary consists of short descriptions of animal life, both real and fantastical. Though they share a similar likeness to modern encyclopedias, bestiaries differed in that they were never meant to be read through a scientific lens but rather of a moral and religious one (J. Paul Getty, circa 2019). To writers and readers alike, each animal was viewed as part of God’s divine plan through evidence of their mere existence. Published in 1607, The historie of fourefooted beastes was no different. It was written by Edward Topsell, a Church of England clergyman, for the purpose of informing, entertaining, and more importantly showcasing the idea that the natural world was created by heavenly intervention (Isaac, 2018). The text was more than just an informational piece, it was a spiritual guide to live by as each animal was paired with lessons and quotes from scripture. The unicorn seen here for example was recognized as a pure beast symbolic of Christ with its capture and death a metaphor for Christ’s crucifixion (J.Paul Getty Museum, circa 2019).

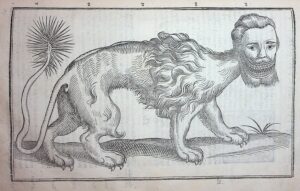

Another example is the infamous ‘manticore’, a mythical creature with the head of a man, the body of a lion, a tail of a scorpion, and a wide mouth that bears three rows of razor-sharp teeth. It is said to live deep underground and finds pleasure in devouring the flesh of men. This creature is of Persian origin with its name derived from an Old Iranian compound word, ‘mand-khora’, meaning ‘man-eater’ (The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2025). In the medieval period the manticore was used in text to symbolise the devil or political corruption.

Topsell, like his predecessors, was not a naturalist but instead borrowed much of his work from others, admitting to have copied from Historiae animalium by Conrad Gessner (Isaac, 2018). This research practice of regurgitating earlier writings was not unique to Topsell. As can be noticed across most bestiaries, there is often a strange and almost comical portrayal of animals throughout. Historically speaking, most artistic representations were simply depictions crafted from the minds of artists based on what they could fashion from the descriptions they read. These (descriptions) which were often pulled from secondary accounts themselves. It was rare, if not impossible, to have first-hand accounts by both author and illustrator, but with the nature of each text being one of religious teaching, it is not shocking that scientific accuracy was of secondary concern. Topsell showcases this philosophy in his introduction, where he pens, “I would not have the Reader … imagine I have … related all that is ever said of these Beasts, but only [what] is said by many” (Isaac, 2018). With this said, Topsell’s work was exemplary and modeled a genre that paved the way for researching natural history. Not only does this piece showcase the beginnings of scientific methodology in the ways of description and artistic display, but it also exemplifies the growth in scientific truth as Topsell cites his sources of inspiration in a pursuit of validation (Isaac, 2018).

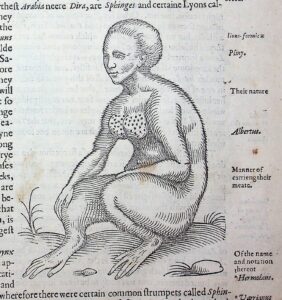

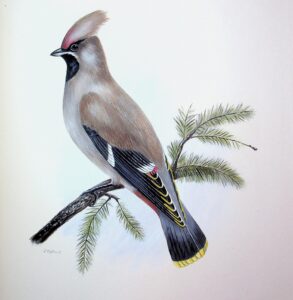

The evolution of the medieval bestiary to modern day research is a long one but can be best shown through the historical lens of ornithology. As mentioned previously, bestiaries by design were tools of religious teaching that blended both scripture and cultural belief. Amongst medieval bestiaries, birds such as chickens, crows, and peacocks were illustrated as symbols in divination, believed to predict times of peace or warn against devastation (MacFarlane, 2020). As an example, caladrius birds (a bird of folkloric creation) made a frequent appearance. Stemming from Roman mythology in the Middle Ages, they were depicted as snow-white birds that resided in a king’s home. It is said that if a caladrius bird was to stare into the face of a sick man, that once they departed in flight, they tore the illness from the afflicted man’s body (Briggs, 2013). The caladrius was seen as a representation of Christ; a virtuous man who in death carried the sins of God’s children to the cross.

It wasn’t until the seventeenth century when the interest in birds moved beyond folklore. Though the study of ornithology began as early as the time of Aristotle, the practice stagnated until the Renaissance when it resurged after the exploration of the Americas brought word of new species of animals and plants. Relying partially on Aristotelian principles, early naturalists classified animals through an avian hierarchy of sorts, grouping birds based on morphology, behaviour, and environmental criteria (Birkhead and Charmantier, 2009). Throughout the 1700s and early 1800s as more species of birds were discovered, the field of research became increasingly specialised. The introduction of Darwin’s theories of natural and sexual selection in the mid-late 1800s inspired a booming interest in the scientific potential of ornithology. This exploration of theoretical possibilities would eventually lead to the birth of modern ornithology in the 1940s and 1950s which formed a harmonious blend of natural history, evolutionary thinking, and systematics (Birkhead and Charmantier, 2009).

From the study of animals, we move on to explore the world of the macabre. In the present day there is a fascination with all things spooky and scary, so much so that an entire commercial sphere has blossomed to feed dark tourism. But where does this morbid curiosity stem from and how did it influence contemporary media?

In early modern England, death had an indisputable connection with Christian belief. With death came Judgement Day, a moment at the end of a person’s life when they stand before God and beg for the forgiveness of sin (Dawson, circa 2020). To promote acceptance into Heaven it was believed that beyond pursuing a pious life, one must also undergo a “good death.” Death was enacted as if it was performance. While lying in their deathbed, a person may impart the gift of wisdom to the living, reminding family members to live in fear of God and honour thy parents. Another might recite the joys of God’s mercy and recount their sins with feelings of true remorse. A charitable act or a display of devout belief was seen as a key that unlocked the doors to Heaven, and to ‘die well’ was a reflection to the living of the successful passage to eternal bliss (Dawson, circa 2020).

A “good death” was a predominately Christian concept that began in 1415 and continued well into the early modern period (Klestinec and Manning, 2024). Death was inevitable of course but after the Black Plague no more than a century prior, the sheer reality of mortality lay heavy on the minds of the living. The plague ushered in disorder and the public display of dying in inhumane conditions. The dead en masse were buried in unmarked grave pits, priests abandoned their duties surrounding last rights, and the sick were left to die alone without the comfort of their family. To die a sudden death, withheld from the gift of the sacrament or confession, left devastating consequences including the weight of potential damnation (Dawson, circa 2020). The gift of a personalised passing became a privilege, one that no one could take for granted.

Subsequent visitations of the plague across the Early Modern period played a powerful role on the literary imagination. With death being so publicly performed in the streets, inevitably death manifested in literature as public, dramatic and metaphorical. Authors such as Shakespeare utilised plague-like metaphors to emphasise the fragility of human life, the existence of moral decay, and the prophecy of social collapse. Literature acted as a microscope that highlighted the collective fears and beliefs of how death gripped its audience. It seemed, though, that there was a sort of obsession with dying, both to perform death in reality and in fiction brought a sort of comfort surrounding the concept of mortality and the blissful reminder of God’s gifts in the afterlife.

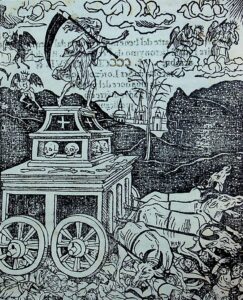

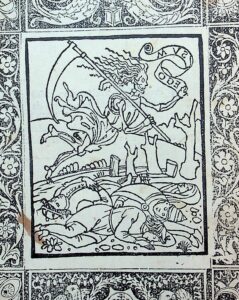

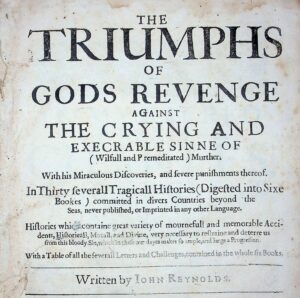

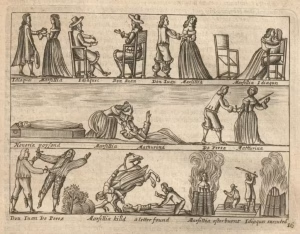

The book shown here is The Triumphs of God’s Revenge, a grotesque compilation of true crime cases showcasing the power of sins such as lust, greed, revenge, and envy to corrupt good Christians. The text follows a pattern of displaying tales of deception, adultery, and homicide framed within the context of God’s triumph over acts of sinfulness (Northwestern, 2021). The Triumphs of God’s Revenge was written in 1621 by author John Reynolds (c.1588-1655?), an English writer and merchant from Exeter. The popularity of this publication inspired five future parts which were collected into a singular volume in 1635. This collection was reprinted in 1639 and 1640, with a second edition of the text displayed here.

St Hugh’s edition of The Triumph’s of God’s Revenge lacks woodcut prints but this was not the case for later editions. As seen in a 1670 edition held at McGill University Library, artistry was utilised in conjunction with the text to add to a more shocking layer of emphasis on each horrific event and the culminating execution of justice. What is fascinating about the pair of text and art is that similarly to other Early Modern texts of the time, the works do not represent an accurate depiction of each crime or even the judiciary process of 17th century England. What it instead highlights is how deeply enmeshed religiously backed morality was with English culture, reminding readers of divine intervention and the inescapable presence God had on his followers.

“Hautefelia causeth La Fresna an Apothecary, to poyson her brother Grand Pre, and his Wife Mermanda, and is likewise the cause that her said Brother kills De Malleray her own Husband in a Duel: La Fresna condemned to be hanged for a Rape; ou the Ladder confesseth his two former Murthers, and says that Hautefelia seduced and hired him to perform them; Hautefelia is likewise apprehended, and so for the cruel Murthers, they are both put to severe and cruel deaths.”

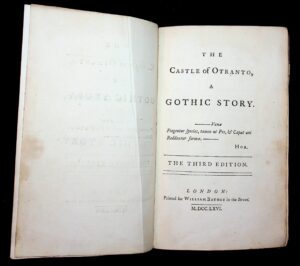

Pictured here is The Castle of Otranto, considered to be the first Gothic novel written in the English language and what spearheaded the horror story as a more legitimised literary medium (Bracken, 2021). Written by Horace Walpole in 1764, The Castle of Otranto was inspired by a nightmare Walpole experienced within his home of Strawberry Hill House in June 1764 (Bracken, 2021). The author claimed he saw the vision of a ghost stating: “I had thought myself in an ancient castle. . .and that on the uppermost banister of a great staircase I saw a gigantic hand in armour” (Lewis, 2018). Drawing on his knowledge of medieval history and the grandeur of Gothic architecture he was so fond of, Walpole penned the now infamous tale of wicked passions, supernatural omens, and the end of an ancient line. Themes and literary devices within The Castle of Otranto would become the blueprint of future novels in the genre including supernatural forces, Gothic landscapes, and hidden identities. Featured here is the third edition of Walace’s work.

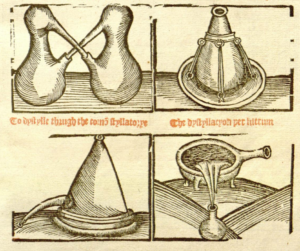

We have learned how death influenced our culture and media, but what about the process of evading death entirely? Of ancient origins, alchemy was a pseudoscientific process that attempted to both transform base metals such as lead into silver or gold, and create elixirs to cure illnesses including death itself (Gilbert and Multhauf, circa 2025). Though a seemingly mystical practice by modern eyes, alchemy utilised the early beginnings of the scientific method through the testing and analysing of hypotheses. The engravings pictured here provided by the 17th c. text The Vertuose booke of Distyllacyon depict the process of distillation. During this crucial step, a liquid substance was boiled in a glass vessel with a long neck called a retort. As the liquid evaporated and the steam condensed, the substance in its vaporized state would collect through the neck of the vessel until it cooled as a liquid into a container on the opposing side (The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2009). It was believed that this process separated the substance from its “volatile impurities” and created a purer substance (Daniel, 2009).

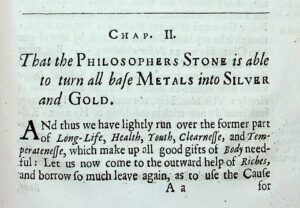

Now a thing of myth and legend, the philosopher’s stone was an obsession of the Early Modern period. According to legend, the substance made of natural material was said to cure illnesses, purify the soul, and even grant immortality (The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2025). From the Middle Ages to the end of the Early Modern period, alchemists attempted to procure this substance, describing the item in question as being of commonly found organic materials simply left untouched and ignored by the common man (The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2025). The fixation on its discovery stemmed from the close relationship Europeans built with death over the centuries due to the plague, a relationship philosophers wished so desperately to be rid of. The infamous alchemist Elias Ashmole, of whom the famous Oxford-based Museum is named, dedicated his life’s work to the cause. The Way to Bliss, on display here, is Ashmole’s final work and argument proving the legitimacy of the stone’s existence (Bauman Rare Books, 2025). Though the philosopher’s stone has since been debunked (to our knowledge), the scientific discoveries made in attempt of finding the stone ultimately created the building blocks for the scientific fields of chemistry and pharmacology (The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2025). This book here is but a representation of that truth, holding a unique history of its own; it was obtained from the library of Sir Isaac Newton, a key figure of the Scientific Revolution.

Lastly we move from the history of death to that of something even more familiar to Britain, the history of our common tongue. Today in England, English is the dominating language of media, literature, and the legal sphere. But it was not always that way and that is in part thanks to the many dominating forces that came to rule the land we stand on.

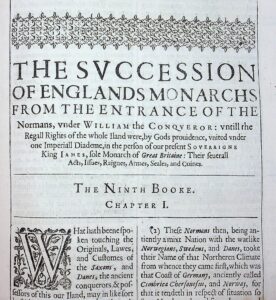

Britain is no stranger to invasion. As seen in Early Modern historical texts, such as the one by Speed displayed here, the English language is a culmination of dialects from indigenous populations to the influence of Germanic cultures and the Anglo-Saxon tongue. The history of the English language is a fascinating one that stems from its personal encounter with domination and cultural amalgamation. Its form and nature as we know it today is largely credited to the Normans and an infamous text titled The Domesday Book (Baker, 2016).

The Norman invasion began after the death of King Edward left England without a direct heir. William, Duke of Normandy, claimed to be next in line due to blood relation. This was swiftly denied by Harold, Earl of Wessex, who after Edward’s death, swiftly took control of the throne. William in response invaded England in 1066, successfully taking control of the crown after the Battle of Hastings (British Literature Wiki, circa 2015). Following his coronation, the newly crowned King William conducted a widespread campaign to legitimize his claim and form deeply rooted allyship amongst prominent points across the country. As part of this project, he commissioned a census known as The Domesday Book in 1086 (Baker, 2016).

Written by the French lawyer, William of Calais, The Domesday Book served two purposes. The first was to create an extensive documentation of the English population for statistical reasons. The second was to understand and establish sway in political environments. Using the French language, Calais solidified William’s ownership of British land granting him the ability to pass claim to nobles supporting his title (Baker, 2016). Over time, William’s influence created a growing divide between the English-speaking public and that of the nobility. The English language that was replaced by Latin in literature and law by the Romans gradually became dominated by Anglo-Norman. It was not until the 13th century that English would make a significant return (Tarlton Law Library, circa 2008).

The dictionary on display was penned by Robert Kelham, an English attorney and legal antiquarian. Within it is a display of Law-French, a language derived from Anglo-Norman and used in the English courts (Tarlton Law Library, circa 2008). Though English would become the primary language of Parliament by the mid 14th century, reports and professional notes were written in Law-French until the reign of Charles II. The last publication to display Law-French was around 1690 with its official end in 1731. (Tarlton Law Library, circa 2008).

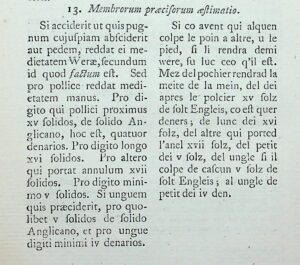

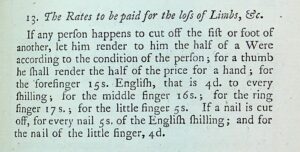

Seen here is an example of medieval law from the period of William the Conqueror. One passage is within the Norman language while the other is in Early Modern English. This specific law regards the punishment of any individual who maims another. For example, if a person was to cut off someone else’s thumb, the price would be the individual’s hand.

“for a thumb he shall render the half the price for a hand”

The Historie of Great Britain is a comprehensive volume by the famous British cartographer John Speed for the purpose of describing the history of the country from its earliest beginnings in the Roman period through to its contemporary period of the 17th century. Throughout the text is an anthropological study of British culture including numerous engravings of seals, weaponry, stylistic dress, geological references, and statistics.

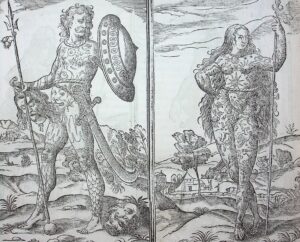

Though one would assume that Speed’s Historie would portray English culture through a strictly positive point of view, his depiction of early British culture is seemingly in opposition to that by modern standards. The images on display here of a man and woman are ‘portraitures of the ancient Britaines’ specifically in their nakedness with unusual paintings and figures marked across their bodies. These engravings are not original to this work but copies from the 1590 edition of Thomas Harriot’s piece A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia (Sayers, 2023).

These individuals represented are artistic depictions of the Picts, or a people from modern-day Scotland. The term ‘Pict’ is derived from the Roman name ‘Picti’ meaning “painted people” which traditionally refers to the practice of tattooing one’s body (Sayers, 2023). It was first used to differentiate between the Roman and non-Roman Britons during the period of Roman occupation. Harriot utilised the images in his history to demonstrate that the early inhabitants of Bretannie were as similarly ‘savage’ to the peoples of the New World. Speed, fascinatingly enough, greatly enjoyed these images and claimed that the Picts were of a distant relation to the Britons as evidence enough to include their artistic representations in his book (Sayers, 2023).

What differentiates Speed’s Historie from that of Harriot’s is that he describes the early British peoples as ‘meerrely barbarous’ and says that their fate was that of darkness, obscurity, and oblivion. He chooses here to create a division between what he deems the more ‘civilised’ British person of his contemporary to that of the past. This severing of ancestral history is then shown quite literally in subsequent editions of his accompanying atlas The Threatre where the Kingdom of Scotland is divided between the Kingdom of the Scots and the Kingdom of the Picts (Dotson, 2025). What is fascinating about this depiction of British history is that it honours the positive influences of what the author defines as more sophisticated cultures (i.e. the Romans and Normans) while creating distance to the roots British culture stems from.

Bibliography

Baker, C. (2016). The Effects of the Norman Conquest on the English Language. Tenor of Our Times, 5(05).

Bauman Rare Books. (2025). Way to Bliss. [Online]. Bauman Rare Books. Last Updated 2025. Available at: https://www.baumanrarebooks.com/rare-books/ashmole-elias/way-to-bliss/81675.aspx [Accessed September 2025].

Biggs, S. (2013). Not Always Bad News Birds. [Online]. British Library. Last Updated: 2025. Available at: https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2012/10/bad-news-birds.html [Accessed August 2025].

Birkhead, T.R. and Charmantier, I. (2009). History of Ornithology. [Online]. Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. Last Updated: 15 December 2009. Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9780470015902.a0003096 [Accessed August 2025].

Bracken, H. (2021). The Castle of Ontranto. [Online]. Encyclopedia Britannica. Last Updated: 2021. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/The-Castle-of-Otranto [Accessed September 2025].

British Literature Wiki. (circa 2015). Norman Invasion 1066. [Online]. British Literature Wiki. Available at: https://sites.udel.edu/britlitwiki/norman-invasion-1066/ [Accessed September 2025].

Daniel, D.T. (2009). Distilling Knowledge: Alchemy, Chemistry, and the Scientific Revolution. Canadian Journal of History, 44(01), 112-114.

Dawson, S. (circa 2020). A Good Death: An Early Modern Obsession. [Online]. Historic UK. Available at: https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/A-Good-Death-An-Early-Modern-Obsession/ [Accessed August 2025].

Dotson, E. (2025). The Life and Works of John Speed. [Online]. Old World Auctions. Last Updated: 2025. Available at: https://www.oldworldauctions.com/info/article/2025-01-The-Life-And-Works-of-John-Speed [Accessed September 2025].

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2025). Philosopher’s Stone. [Online]. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Last Updated: 9 September 2025. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/philosophers-stone [Accessed September 2025].

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2025). Manticore. [Online]. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Last updated: 21 January 2025. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/manticore [Accessed August 2025].

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2009). Retort. [Online]. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Last Updated: 28 August 2009. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/technology/retort [Accessed October 2025].

Gilbert, R. A. and Multhauf R.P. (circa 2025). Alchemy. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/alchemy [Accessed October 2025].

Isaac, S. (2018). The familiar and the fantastic: The historie of foure-footed beastes by Edward Topsell, 1607. Royal College of Surgeons of England. Last updated: 16 March 2018. Available at: https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/library-and-publications/library/blog/the-familiar-and-the-fantastic/ [Accessed August 2025].

- Paul Getty Museum. (circa 2019). Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World. [Online]. J. Paul Getty Museum. Last

- Updated: 2019. Available at: https://www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/bestiary/inner.html [Accessed September 2025].

Klestinec, C. and Manning, G. (2024). The Good Death in Early Modern Europe. History Compass, 22(08).

Lewis, W. (2018). Choice 19: Cole’s Copy of “The Castle of Otranto”. [Online]. Yale University. Last Updated: 2025. Available at: https://campuspress.yale.edu/walpole300/31-choice-19-coles-copy-of-the-castle-of-otranto/ [Accessed September 2025].

MacFarlane, R. (2020). Bird-spotting from medieval to modern times. [Online]. Welcome Collection. Last updated 20 April 2020. Available at: https://wellcomecollection.org/stories/bird-spotting-from-medieval-to-modern-times [Accessed August 2025].

Northwestern. (2021). Introduction. [Online]. An Inquisition for Blood: Tales of Murder and Justice in John Reynolds’ The Triumphs of God’s Revenge. Last Updated 2021. Available at: https://sites.northwestern.edu/murther/ [Accessed September 2025].

Ostberg, R. (2025). Memento Mori. [Online]. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Last Updated: 10 September 2025. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/memento-mori [Accessed August 2025].

Sayers, K. (2023). The Ancient Britains in John Speed’s ‘The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britain’. [Online]. Leeds University Libraries Blog. Last Updated: 15 March 2023. Available at: https://leedsunilibrary.wordpress.com/2023/03/15/the-ancient-britains-in-john-speeds-the-theatre-of-the-empire-of-great-britain/ [Accessed September 2025].

Tarlton Law Library. (circa 2008). Robert Kelham (1717-1808). [Online]. Tarlton Law Library Jamail Center for Legal Research. Last Updated: 9 May 2024. Available at: